Scratch-Off: Ms. Shirley Jackson at SU

She was a lonely student, in a new town, during an interesting time. In 1937, Shirley Jackson, whose short story “The Lottery” would soon become obscenely popular, was habitually alone. Her year at the University of Rochester had been disheartening, indeed, almost maddening, but she wrote in her application to SU that she “wish[ed] to further her writing career.” And she would, but not in the way that you might think.

“The Lottery” stands today almost as well-known a Cold War parable as Arthur Miller's play, The Crucible. Indeed, writers are still influenced by the stark tale of a woman randomly chosen to be stoned to death – sacrificed – for the good of her town. For example, in Colson Whitehead's 2016 novel, The Underground Railroad, he pays homage to the chilling ending of “The Lottery.” As the townspeople recapture an escaped slave, “Two more children picked up rocks and threw them...the town moved in and then Cora couldn't see them anymore.”

One thing that separated The Crucible and “The Lottery” was the timelessness of Jackson's violence, which may have been the reason for so many negative reactions. While The Crucible was about a real witch hunt, the dangerous ones in “The Lottery” were ostensibly fictional townspeople – perhaps even the readers? Jackson herself was called a witch, a persona she did not publicly quibble with. And why bother? This was the age when, for Miller and many others, it was the witch-hunters who were evil. An Associated Press reporter commented that Jackson “wrote not with a pen, but with a broomstick,” but her reputation hardly suffered for it.

Ruth Franklin's 2016 biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, is an illuminating look at a woman whose stories and psychological makeup have been explored in detail before, but whose family life, until Franklin, biographers have overlooked. This despite her many columns about being a wife and mother, collected as Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. However, the depth of Jackson's troubled relationship with her husband was something she never wrote seriously about. Franklin has done a superb job reading Jackson's lines (and between them), and argues that, as a woman in the mid-20th century, her marriage to Stanley was the most terrifying thing of all.

Chapter Four is called “S & S: Syracuse, 1937-1940,” and it is about Jackson's undergraduate years in the English program. It is also where Shirley meets her future husband Stanley, and ends with the two of them moving to New York City to become writers. But an incident that remains murky occurred her senior year when her department shut down the literary magazine they created. It makes sense of Stanley's later contrarian satisfaction that “the college was glad to be rid of both us and the magazine,” and adds a touch of irony to Shirley's statement to the Daily Orange in 1965 that “my education at Syracuse started me writing.”

When I saw that Jackson's new biography was coming out, I was riveted. I was not familiar with Jackson's other works, let alone the story of her life. But the few pages that comprised “The Lottery” had shaken me and never let go. I was always drawn to horror, but the blood-soaked tales of Stephen King and Clive Barker felt like something else. This “old lady's” subtlety shocked me and her implied violence were more relatable and less apt to be romanticized, but just as scary as the Masters.

You see, when I began middle school in a rural district, the bullying was constant. The dread that came with me to school many mornings seemed much larger than me. I stood at the end of the long, dark and empty hallway on the first day and the first person who walked toward me as I tried to open my locker grunted, “Fucking faggot.” He didn't lunge at me or even veer in my direction, but the sense of menace that he projected was threatening nonetheless. And no one came to help me. There was violence in his words. They weren't upon me yet, but they were before too long.

Judging from her photo in the 1940 Syracuse University yearbook, The Onondagan, Shirley Jackson's three years at Syracuse University were relatively uneventful. While the eight students' pictures around her all boast of membership in Greek organizations, only her major is listed.

Shirley had left the University of Rochester after an unsuccessful freshman year. She had made some friends and dated, but lived with her parents, and soon her grades began slipping. Burnt out, she left school and began a strict writing schedule of 1,000 words a day. She applied to Syracuse University in 1937. Syracuse had a reputation for being a bit wilder than the U of R. Her Rochester boyfriend, Michael Palmer, had called SU “a hotbed of communism and antisocial attitudes.” But for the first semester Shirley remained a loner in the small library listening room.

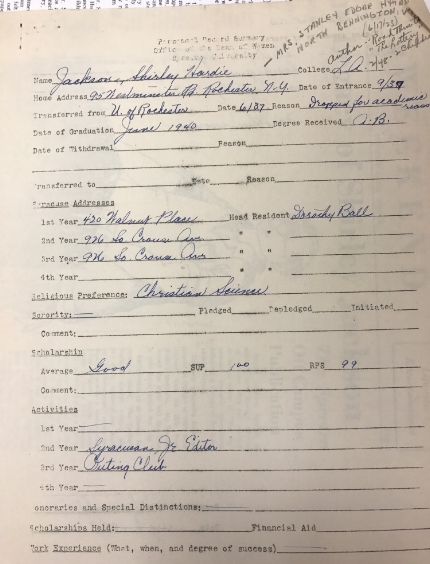

Jackson's application to Syracuse University. Since it asks, she notes she was a girl scout.

Writing had been the center of her life for a long time. She had kept a diary since she was a young teenager and wrote for pleasure, but hardly received any praise from her family for her efforts. After reading them a particularly interesting story, the responses ranged from her brother's “Whaddyou call that?” to her father's 'Very nice.' Her mother wondered if she had “remembered to make the bed.”

Now, for the first time in her life, she was away from her unsupportive parents. Soon Professor A.E. Johnson's creative writing class gave her an outlet to write and meet new people. She and a friend explored downtown, including “the swanky Yates hotel,” and Shirley wrote in her diary that “I have been relaxing into myself. I do not feel the constant strain to be someone else.”

Campus life in the late 1930's shared many similarities with today. Frat houses lined Walnut Avenue, and students hung out on “the hill” at places like The Cosmo, an all-night coffee shop known to students as “The Greeks.” The Daily Orange had been a newspaper since 1903.

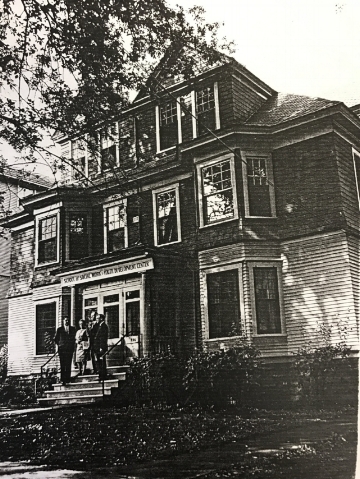

Instead of dorms, female students lived in "cottages." Pictured is Lima Cottage, (926 South Crouse Avenue), where Jackson lived.

She wrote a piece called Janice that the campus magazine printed. Barely a page long, the story is about a college student who casually chats with a friend about committing suicide. The almost throwaway line, “Darn near killed myself this afternoon,” was hallmark Jackson. Although it was not a political piece, it captivated Stanley Hyman, a fervent left-wing literature student who introduced himself to Shirley immediately and, Franklin writes, told her, “you were the only live thing I had seen outside the greenhouse all winter.”

Shirley and Stanley began dating. They shared literary interests but were not aligned in subject or style. Stanley was a member of the Young Communist League who, at one point, spent time trying to organize steelworkers in Solvay. His writing was directed solely toward the class struggle and disdained apolitical writing. At one point he told Shirley, “i [sic] think you are potentially the greatest writer in the world, [and] wish you had something to write about.” This despite most people agreeing that Shirley was by far the finer writer of the two.

Yet they started a campus literary magazine called Spectre with some friends (and the backing of the English Department). In the editor's introduction, Shirley jokes that she and a group of friends were hanging around “trying to think of some way to pass a long hard winter.” “Let's tie friends in chairs and read our stories to them,” she reports Stanley replied with a grin.

The magazine mostly published short stories. One of Jackson's, “Call Me Ishmael,” was about the narrator's frustration at the difficulty of communication with her mother. They look across a street at a woman (presumably a prostitute) and cannot even agree how to talk about her, as if they speak different languages, or exist in different worlds. Another story was Shirley's humorous essay, “My Life In Cats.”

At the same time, this was 1939, and war was everywhere. Yes, there were a few passing allusions, like the story “Land Of The Pilgrim's Pride,” about an Austrian refugee trying to make enough money to send back to his family. But most of the overt political commentary in Spectre was about the University itself.

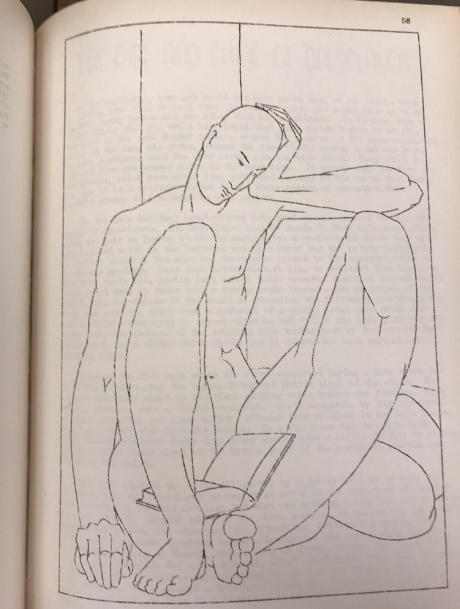

In only its third issue, the “We The Editors” section announced, “Here we are, already a magazine with a lurid past.” After a short run, the University would shut Spectre down. “It seems we had two pictures of two nude male bodies, and if you want to have nude bodies in a campus publication, without corrupting public morals, they have to be female bodies.” Interestingly, the editorial goes on to make the magazine's most direct reference to Hitler and what it meant for intellectual freedom on campus. “The college cannot, must as it tries, avoid reflecting some measure of contemporary social and political reality. Today there is a war, with half of Europe under arms and the other half scared stiff (you may have heard of it).”

The denunciation of racial segregation at SU in Spectre I, no. 4 (Summer, 1940).

But in her biography of Jackson, Franklin theorizes that the drawings did not close down Spectre. She writes that it was Shirley herself who tipped off the magazine's faculty adviser about the nudes in order to generate controversy and doesn't think the plan would back-fire that completely. Another possibility was the critical attack on Prof. A.E. Johnson's poetry in its pages – anonymous, but probably made by Shirley and Stanley. But Franklin discounts this theory too. The politics of the college that Shirley did comment on the most was discrimination against black students. The editors observed that Marian Anderson had performed at the school, and in fact, “sells out every time she comes here, but they won't allow negro girls in the college dormitories.” This was playing with fire.

In this critique Jackson was just barely ahead of her time. In a 1984 scholarly article, “Discrimination at Syracuse University,” Harvey Strum analyzes how drastically the university's policies about race and sex changed after 1942, when William Tolley became Chancellor. The path toward inclusion was not straight, and depended much on who led the University. In fact, in the early 20th century, Chancellor James Roscoe Day had battled uphill against bigotry, telling John D. Rockefeller, “We welcome Jew, Gentile, Protestant and Catholic.”

William Pratt Graham, an electrical engineering professor and sixth chancellor of SU.

Then, in the 1920s, racism and the Nativist reaction against immigration began to affect policies at SU. Vice Chancellor, and later Chancellor William Pratt Graham, instituted discriminatory admissions and housing policies for African-Americans, Jews, Catholics and women. This was in line with many other American universities, and according to a Daily Orange investigation at the time, in accordance with many of the students' beliefs. Graham, himself an 1893 graduate of SU, convinced the Director of Admissions, Eugene Bradford, that including photographs with applications was required to avoid accepting students who shouldn't represent the University. After all, “his certificate is generally the same color as a white man's.” Bradford suggested adding to applications the directive, “If other than a native white American citizen, state race and nationality and enclose a photograph.”

It wasn't until two years after Jackson graduated that Tolley ascended to the chancellorship and began to direct the roll-back of Graham's exclusive policies. By that time there were only three black students left at SU. Stanley belonged to the only Jewish fraternity. Interestingly, a top-down order had also cut the number of women allowed into the university, especially in the English Department of the late 1930s, when Shirley attended. Understandably then, as Shirley and Stanley left Syracuse in 1940 to move to New York, they didn't look back. Chancellor Graham left the University too, but became a member of the Syracuse Common Council.

An edited Syracuse University transfer document notes that Jackson wrote The Lottery and became Mrs. Stanley Edgar Hyman.

Jackson and Hyman remained husband and wife until she died in 1965. The central argument of Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life is that she was scared, not of the beyond, but of the here and now. She and her husband shared an intellectually stimulating life together; that much is clear. She also adored him, and indeed, supported him with love and money when his books failed, numerous times, to support the family, both because they were specialized works of literary criticism and he could never seem to make deadlines.

Still, Hyman was consistently and openly adulterous. The pain that Shirley suffered as a woman from his treatment (and society's), would haunt her, Franklin argues, for her entire life. Stanley was not only incredibly condescending towards Shirley's writing, but thoroughly dependent on her for domestic needs. Some said that he could not even make a pot of coffee. It's not a coincidence, Franklin notes, that the woman who dies in “The Lottery” was late because she had been at home washing dishes. The irony of Hyman's statement while they were still at Syracuse, that she had nothing to write about, is now clear. Jackson was writing about him; alas, she wrote not with a broomstick, but with a pen.

This drawing, from Spectre I, was not one of the two "offensive" pictures, which were removed from the magazine.

All of this came after Shirley Jackson graduated from Syracuse University, yet I see a thread running between the Spectre affair and her life with Stanley. On April 28, 1965, the headline of The Daily Orange was “Jackson Credits SU With Writing Start.” “But most of my class compositions came back criticizing me for confusing 'that' and 'which,' she added with a laugh.”

Did the University ban Spectre because of its editorial positions against racial discrimination? The drawings? Or for biting the hand that fed them, Prof. Johnson? We'll probably never know. That they are all plausible gives one pause. Since the appearance of nude drawings was the given reason, it is worth exploring what it says about history as well as the present.

It may be tempting to equate the shuttering of Spectre with that of the SU's racist-joke smeared Hill TV channel in 1995. Political correctness run amok, some say. But I would disagree. At the end of “The Lottery,” as the village closes in on the “winner,” Tessie Hutchinson, with rocks at the ready, she screams, “It isn't fair, it isn't right.” Jackson says nothing about political correctness, the accusation of which has been too often used as an either a euphemism or epithet to comfort the feelings of straight white men. The victim of hate speech does have reason to worry that violence may follow, at SU and anywhere else.

Most of the talk about political correctness recently has been about whether Muslims are dangerous to democracy. ACT for America's anti-Muslim rally, which took place in Syracuse on June 10th, is pertinent in that its members seem to assume that American men have consistently and altruistically acted for womens' best interest, and still do. The protest was formally billed as an anti-Sharia law event, but as many have noted, there is no danger of Sharia law governing Americans. Still, for these 21st century patriots, the cry for the veil to be torn off seems reasonable. Our claims of progress are as American as “mom and apple pie.” Because here, ladies are still free to wear as little as they want. It's a free country, right? (It's true; all the guys are saying so!).

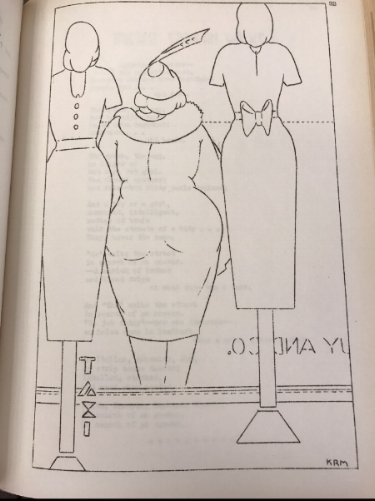

Another example of body image expectations from the 1930s.

But according to a Spangle magazine article “Why Is The MPAA So Concerned About Male Nudity?,” the opposite is not true. Displaying a naked man is still taboo in a way that it just isn't so for a naked woman, and hasn't been for a long time. “Think of how many times you've seen a naked woman in a film as compared to a man; that's because straight men are turned on by the sight, and women aren't turned off. Homophobic Hollywood doesn't think the same is true of the opposite, so naked men are a rarity.” When I went to an art exhibition called “The Sexuality Show” in Corning, New York last year, there were no images of nude males. It's obvious which gender benefits from allowing the exposure of naked women while practically banning that of naked men.

Of course, if the study “Discrimination At Syracuse University” were done now, it would look very different. We might be asking whether the pictures were censored because the male bodies stirred up fears (or worse, desire?) of and for queerness that the University wanted to squash. After all, until very recently, outing a gay person created professional as well as a personal liability.

In 1937, the same year that Jackson entered Syracuse University, Grant Wood, the artist known for his 1930 painting, “American Gothic,” revealed his lithograph, “Sultry Night,” which showed a naked farmhand cooling off with a bucket of water. His distributor, the Association of American Artists, condemned the piece as did the U.S. Post Office, as being obscene. Wood's sexuality was subject to gossip in newspapers and magazines and at the University of Iowa, where he taught, but his sister's later burning of his letters prevented confirmation of the rumors.

In any case, the illustrator of the first issue of Spectre was a woman named Florence Shapiro. Shirley despised Florence, and soon replaced her, because she found Florence and Stanley alone in his room, where he had invited her after repeatedly praising her figure. Marital relationships such as Jackson's and Stanley's were also seen differently then. Franklin's book is testament to the fact that that many of the most progressive intellectuals had what we would call major blind-spots and – and so might we.

A "Junior Beauty" from The Onondagan yearbook.

One final bit of Shirley Jackson history is instructive here. The editors of Spectre made a list of snobby yet bitingly funny observations about SU called, “22 Propositions Illustrating the Cultural Level of Syracuse Students.” Number one is, “They object to the lack of good lighting in the library, but don't bother about the lack of good books.” And then number 16 bewails, that “The same students who thought Mice and Men and Grapes of Wrath were depressing spent four hours watching Scarlett shoot off the front of a soldier's head.” The last, number 22, reads simply, “Junior Beauties.”

Amid the pages of The Onondagan yearbooks during the years Jackson attended were full-page photographs of female students deemed “Junior Beauties,” a kind of a “page 3 girl” feature that flaunted these women as advertisements – as objects to be possessed. It seems that Jackson saw this feature for what is was, and her derision speaks for itself. But when the next anti-Muslim march comes to Central New York, we should all remember that although life is indeed a lottery, we retain some choice of who we speak for, and how we play the game.

ACT for America rally outside the James M. Hanley Federal Building on June 10, 2017.

I would like to thank my friends and colleagues in the Downtown Writer's Workshop for all of their wonderful feedback. Thanks also to Nancy Keefe Rhodes for teaching the class and editing this piece.